In my decade-ish long wine journey, I never worried too much about the number of women producing delicious wines and driving the industry forward, especially as so many of my favorite female winemakers are producing standout bottles. My collection has always included bottles from the legendary Cathy Corison, volcanic Sicilian wines from Arianna Occhipinti, and the graceful Fleurie of Beaujolais’ Anne Sophie Dubois. Even among the new guard of U.S. west-coast winemakers, Martha Stoumen, Megan Bell, Brianne Day and Kelley Fox are among my favorites. As a wine geek located in D.C., my favorite day trip recommendation is Early Mountain, where Maya Hood White has transformed the vineyards and produces some stunning examples. And my summer go-to quencher is currently a bright Albariño from Blenheim Vineyard’s Kirsty Harmon from the Monticello Wine Trail.

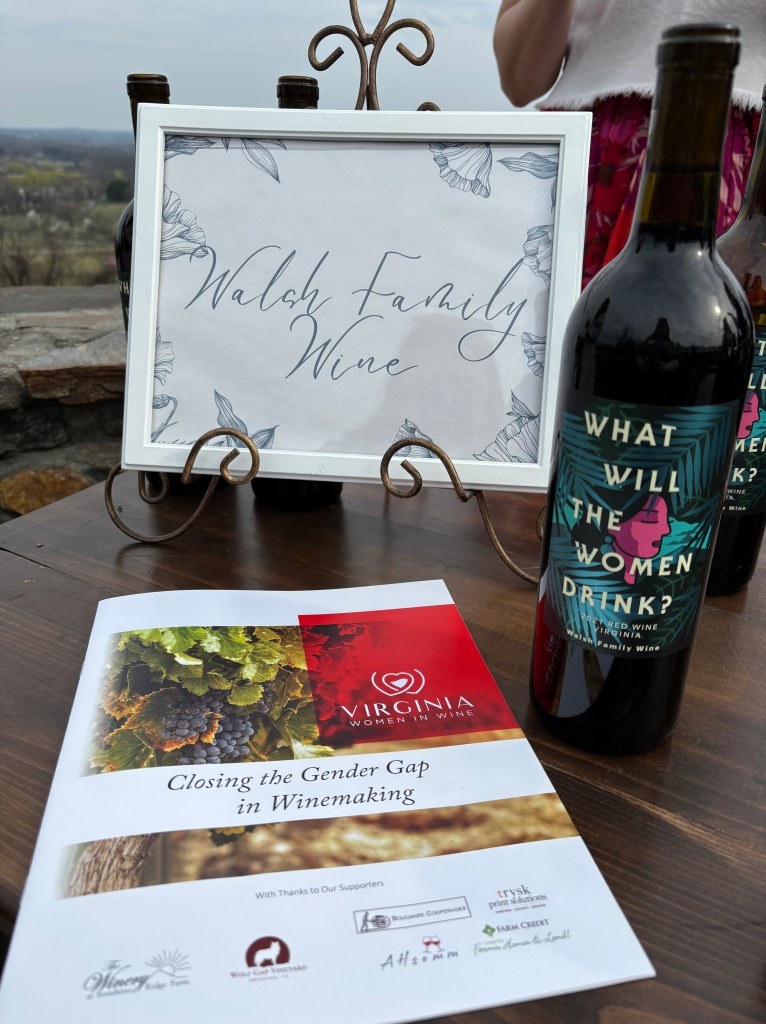

So when I was asked to write a white paper about closing the gender gap in winemaking for the Virginia wine industry, I was surprised to learn that only about 17% of winemakers in the U.S. are women. In Virginia, the statistics for female winemakers are nearly the same, although if you dig deeper to understand hiring, the chances for a woman to become a Virginia winemaker are far more likely if she has the resources to start her own winery. In the last five years, according to data tracked by Matthew Fitzsimmons, only two women were hired by wineries they had no relation to.

Barriers Facing Female Winemakers

Finding out the answers why, and identifying solutions to achieve gender parity, is not easy. One woman who confided in me, shared her career trajectory was a mix of impressive support from some of her bosses, yet a number of different kinds of challenges ultimately led to her decision to step away from winemaking.

For example, early in her career, she was often singled out to do gender-biased tasks like cleaning up “after the boys.” As her career progressed, she said men with less experience would surpass her for winemaking roles, and once finally becoming a winemaker, she still faced questions of whether she could do the job. Combine all this with a lack of health benefits (leading to her questioning whether she wanted a family), and a role requiring long hours, with little to no overtime pay, it’s easy to see why she decided to move her career in a different direction.

These are hard decisions. Winemaking is a passion industry and often a form of personal artistry, where the drive to succeed can be far more personal than those entering more traditional corporate career paths.

What’s curious is that women often make up more than 50% of enology degree programs, yet far fewer become winemakers. When I reached out to some administrators at U.C. Davis’s enology program, they pointed to what could be one of the biggest challenges to closing the gender gap: Anecdotal evidence suggests women leave winemaking within 5 to 10 years of graduating at a higher frequency than men.

Challenges for female winemakers often came down to sexist attitudes that women can’t physically do the job (which to put it bluntly by many of the women I interviewed, is “bull sh*t.” ), the lack of benefits and job security, not getting paid the same as their male counterparts (although national salary data — which include the E&J Gallos of the world alongside the smaller wineries — shows salaries between the genders are not too far off), and women having to work harder to constantly “prove themselves,” often with little recognition for it.

Strengths Women Bring to the Cellar

What makes these conditions even more frustrating is when you understand the many strengths women bring to winemaking: They have more innovative ideas (perhaps because of the legacy of having to prove their worth), they have strong collaborative skills (and as one male winemaker noted, “less drama” in the cellar), and they possess innate skills lending to better quality wines (studies show women can be better tasters; and a few winemakers I’ve spoken to over the years point to women being much better nurturers, aiding in the patience that’s needed in both the vineyard and the cellar to make quality wine).

The good news is that success can be found, often by finding the right mentors. Most of the female winemakers I spoke to were able to successfully navigate the industry by having mentors who provided everything from practical winemaking advice, to leadership skills, to how best to handle working relationships in the industry.

In the paper, I briefly highlight a few mentoring and training examples, including that of one woman who started her career washing dishes in the winery, moved to the vineyard and is now training to become a winemaker alongside the winery’s head winemaker who said she was now his “right-hand person,” contributing to the quality of the wine.

Visibility and Lasting Change

In their book “Women Winemakers: Personal Odysseys,” Santa Clara University professors Lucia Albino Gilbert and John Gilbert came to the conclusion that a key solution to bringing more female winemakers in the field is more visibility. Whether that encourages more women to enter the field or those in the industry to be more accepting, I tend to agree. But it’s also the easy answer. The challenges women face in the U.S. (and in Virginia) are complicated and ones that a one-size-fits all solution can’t address. But if we can get the conversation started, and showcase the immense talents that women bring to the industry, perhaps in a few years, the data will say something different.

Read the Full Report

For the paper Virginia Women in Wine commissioned, we let the voices of Virginia’s wine industry shine through and hope it serves as a launching point for hiring managers and other industry leaders to create a more inclusive and diverse industry for women and future winemakers. Download the “Closing the Gap in Winemaking” PDF here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.